Use TypeScript Record Types for Better Code

The TypeScript Record is one of my favorite utility types in TypeScript that I find to be under-appreciated.

When leveraged to its potential, it can help teams write better, less error prone, more maintainable code whether you’re using TypeScript in the back-end or the front-end (and especially so if you’re using it at both!); I promise you that you’ll be on your way to writing better code in less than 5 minutes.

The documentation for this utility type is quite sparse:

Constructs an object type whose property keys are Keys and whose property values are Type. This utility can be used to map the properties of a type to another type.

And it doesn’t expose the Record type’s true super power: enforcing exhaustive case handling.

Let’s take a look and see how we can use this feature to write better code with a simple React example.

Understanding Record Types

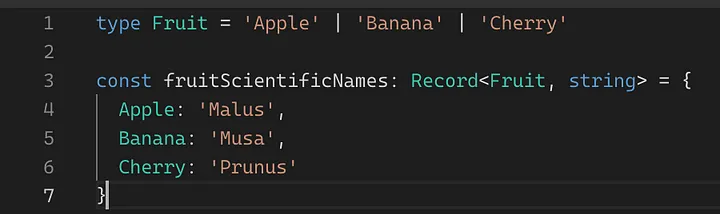

If we define a type like so:

type Fruit = 'Apple' | 'Banana' | 'Cherry'And then use the type as the key of a Record:

const fruitScientificNames: Record<Fruit, string> = {}We’ll notice that TypeScript immediately gives us a warning:

TypeScript expects the Record to have an entry for each of the values defined in the union Fruit.

TypeScript expects the Record to have an entry for each of the values defined in the union Fruit.

To fix this, we need to add an entry in the Record for each Fruit: Now our error is cleared up.

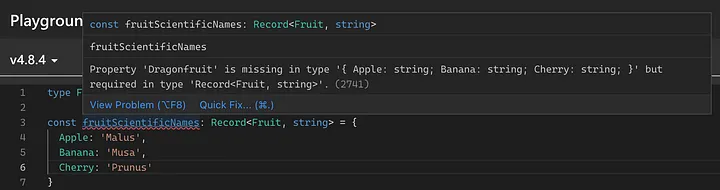

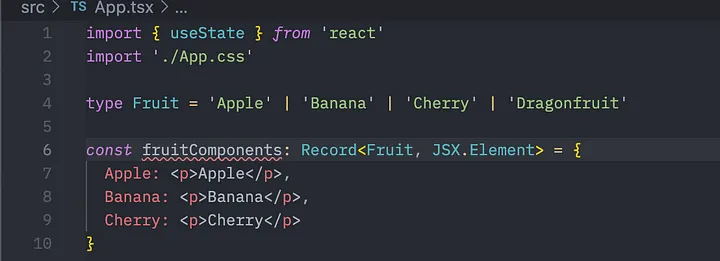

If we add another entry into Fruit:

type Fruit = 'Apple' | 'Banana' | 'Cherry' | 'Dragonfruit'

const fruitScientificNames: Record<Fruit, string> = {

Apple: 'Malus',

Banana: 'Musa',

Cherry: 'Prunus'

}Once again we get an error because we haven’t added an entry for “Dragonfruit”:

TypeScript will require us to add an entry for Dragonfruit into our Record.

TypeScript will require us to add an entry for Dragonfruit into our Record.

This is interesting in and of itself, but how can we exploit this property of Record types to write better, more maintainable code?

Doing More with Record Types

One additional thing to understand is that we are not limited to strings in a Record; we can can hold anything in the value slot like a function:

const fruitWriter: Record<Fruit, () => void> = {

Apple: () => console.log('Apple'),

Banana: () => console.log('Banana'),

Cherry: () => console.log('Cherry')

}// Now we can invoke like this:

fruitWriter['Apple']()The Record now maps a Fruit to a function which takes no arguments and returns no value.

But we are not limited to simple functions, we can of course specify parameters:

// Function to lowercase an input string.

const lowerFn = (text: string) => text.toLocaleLowerCase()

const lowercaseFruitWriter: Record<

Fruit,

( fn: (text: string) => string ) => void

> = {

Apple: (fn) => console.log(fn('Apple')),

Banana: (fn) => console.log(fn('Banana')),

Cherry: (fn) => console.log(fn('Cherry'))

}// Prints 'apple'

lowercaseFruitWriter['Apple'](lowerFn)and return types:

const lowerFn = (text: string) => text.toLocaleLowerCase()

const lowercaseFruitWriter: Record<

Fruit,

( fn: (text: string) => string ) => string

> = {

Apple: (fn) => fn('Apple'),

Banana: (fn) => fn('Banana'),

Cherry: (fn) => fn('Cherry')

}

console.log(lowercaseFruitWriter['Apple'](lowerFn))With this, we can do far more interesting things now like build and return React components, define a list of validator functions, or in general perform some Fruit specific operation.

Less Error Prone Code

In many cases when building a UI or back-end logic, there will be situations where the code must perform some action based on a discriminator value.

Very typically, this will be done with a switch-case or if-elseif-else.

function fruitPrinter(fruit: Fruit) {

switch (fruit) {

case 'Apple':

console.log('apple')

break

case 'Banana':

console.log('banana')

break

default:

console.log('')

}

}Aside from being more verbose, the real problem here is that if we add another value to Fruit, we won’t be notified of the all places where we need to update our code to handle this new case. Instead, at runtime, the code will fall into the default block and present the user some undesired behavior.

Wouldn’t it be nice if every time a new Fruit was added, the compiler notified us of all the places in code that need to be updated as well?

With Record, we would find these gaps at compile time and write safer code.

We can take advantage of this in React instead of using conditional rendering using switch-case or if-else:

A very simple example of how we can use the Record to ensure we always have a component for the Fruit. Notice what we didn’t need: if-else or switch-case!

A very simple example of how we can use the Record to ensure we always have a component for the Fruit. Notice what we didn’t need: if-else or switch-case!

Our simple app and components

Our simple app and components

But the real win here is that adding “Dragonfruit” now results in an error at dev/build time:

Our Record is missing an entry for “Dragonfruit”

Our Record is missing an entry for “Dragonfruit”

In even a moderately sized codebase, this can make a big difference in correctly handling new cases since introduction of a new option would immediately alert us where we have to add handling for that option in our codebase.

The Record type’s true super power: enforcing exhaustive case handling

Consider that instead of fruits, our options are IdentityProviders or DatabaseTypes or ApiEndpoints. Using a Record, we can easily ensure that whenever new options are added, both the front-end and back-end correctly handle the new cases at dev/build time instead of runtime.

Not only did we make the application easier to maintain thanks to TypeScript’s enforcement of exhaustive case handling, we’ve also shifted the flow of the code from procedural to structural; in other words, we use structure to dictate flow of control.

If you’d like to see an example of how to use the Record type to create a Factory design pattern, check out my other article: Structural Control Flow with Object-Oriented Programming:

// The Record holds a constructor; how cool is that?

const shippingStrategies: Record<

ShippingMethod, {

new(weight: number, hasLiquid: boolean): ShippingStrategy

}> = {

USPS: UspsShippingStrategy,

UPS: UpsShippingStrategy,

FedEx: FedExShippingStrategy,

DHL: DhlShippingStrategy

}I hope that this short take on TypeScript’s Record type helps you understand how to leverage its hidden super power to write better, more maintainable code! Both front-end and back-end teams using TypeScript can utilize this simple construct to dramatically increase maintainability and correctness while also simplifying code with virtually no additional lift!