3 Tips to Help Dev Teams Build Speed

Just three simple tips to help dev teams ship software faster. Mostly for small and medium sized teams, but probably just as applicable in larger organizations.

Simplify, Simplify, and Simplify Some More!

You Aren’t Gonna Need It or YAGNI is a term that sums up much of the accidental complexity that teams end up mired in. My observation is that there there has been a tendency towards engineering solutions that add complexity to solve perceived problems today or possible problems in the future. This complexity, when introduced too early, becomes a source of friction that slows teams down and makes the team less nimble.

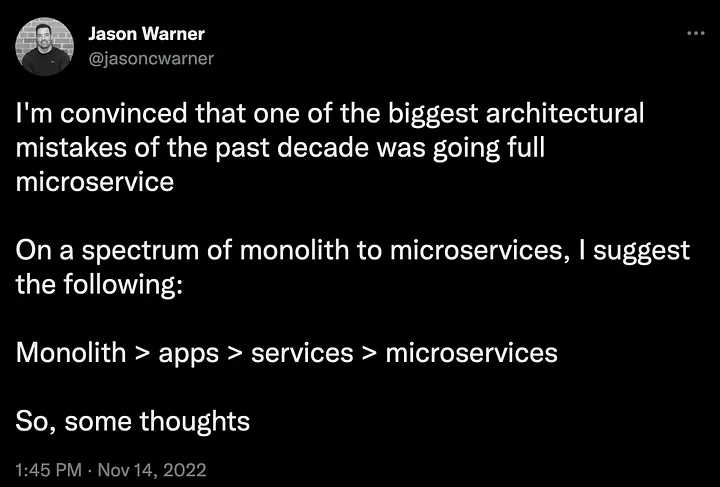

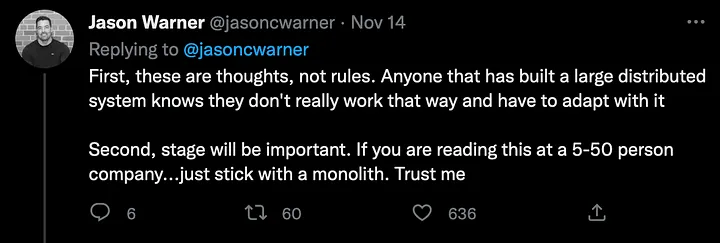

For example, Jason Warner — former CTO of GitHub — had this to say about microservices:

Read the thread for more thoughts from Jason on microservices vs monoliths.

Read the thread for more thoughts from Jason on microservices vs monoliths.

I’ve written before on the related topic of embracing the mono-repo. While they are orthogonal concerns —microservices being concerned with how software is deployed and mono-repos being concerned with how source is managed — the heart of problem is the same: the more a team’s workflow is fragmented, the more friction it creates and the slower every action becomes, especially for small teams.

I agree: mono- is generally the best option for most small to medium sized teams.

I agree: mono- is generally the best option for most small to medium sized teams.

One of the reasons that EVs are gaining traction now — disjointed of environmental considerations and consumer demand—is that once the engineering hurdles and market forces are worked out, it is simply more economical for the manufacturer. Jim Farley — CEO of Ford — cites a 40% reduction in the number of workers required to assemble EVs compared to ICEs due to simply having less parts to acquire and assemble.

The same is true of software; the greater the number of complex moving parts that are required to build and ship the software, the larger the teams have to be to wrangle the complexity (until the management and coordination of those teams introduces yet another layer of complexity).

Early on in the lifecycle of a project — whether startup or enterprise — there is always a period of discovery and learning where the requirements are not quite clear, the specifications are still materializing, the use case is missing some edge cases, or some assumptions are simply wrong. If fragmentation and complexity are introduced early in this process, it creates drag on every action and reaction to the inevitable changes that come down the pipeline.

This also holds true for not just how code is organized and deployed, but also the architecture of the system and the stack on which it is built.

Ken Kantzer has an insightful article 5 Software Engineering Foot-guns that succinctly summarizes my own experiences and thoughts on systems complexity:

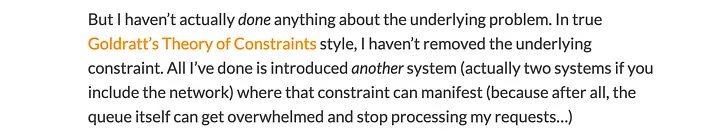

Kantzer’s foot-gun #4: Not properly respecting the complexity of distributed systems

Kantzer’s foot-gun #4: Not properly respecting the complexity of distributed systems

It is often the case that an attempt to isolate some complexity by fragmenting it simply shifts the complexity and adds more connective complexity!

Stephan Schmidt’s recent article Just Use Postgres for Everything is a really good example of the kind of insight that can help teams rethink accidental versus necessary complexity.

One way to simplify your stack and reduce the moving parts, speed up development, lower the risk and deliver more features in your startup is “Use Postgres for everything”. — Stephan Schmidt

It is not so much about Schmidt’s endorsement of Postgres, but the underlying insight to avoid adding more complex moving parts that need to be managed and owned until such time the benefit of adding those parts warrants the overhead of additional attention, knowledge, and skill fragmentation/specialization. In other words, frame your stack choices carefully and evaluate each additional moving part with a critical eye focusing on the right amount and right type of complexity at the right time.

Work Asynchronously As Much as Practical

Over two decades ago in Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams, Lister and DeMarco wrote about the effect of a software developer’s environment on productivity. The door to a room is a very physical and visceral indicator of the modes of interaction one is in the mindset for. The option to open the door or walk to shared space to chat and interact provides the choice to interact synchronously.

DeMarco and Lister cite an experiment they conducted on the effect of the workplace on a developer’s performance:

The top quartile, those who did the exercise most rapidly and effectively, work in a space that is substantially different from that of the bottom quartile. The top performers’ space is quieter, more private, better protected from interruption, and there is more of it. (p. 47, Peopleware, DeMarco, Lister)

Since their publication, it seems the world has gone the other way with tightly packed open office plans that provide little room for deep thought and adoption of communication tools that create an expectation of synchronous modes of dialogue.

For software engineering teams, there is a balance between the collaborative, creative ideation phase that needs to be managed against the need to carve out space for deep focus — or flow — during implementation.

The phenomena of flow and immersion give us a more realistic way to model how time is applied to a development task. What matters is not the amount of time you’re present, but the amount of time you’re working at full potential. An hour in flow really accomplishes something, but 10 six-minute work periods sandwiched between 11 interruptions won’t accomplish anything. (p.63, Peopleware, DeMarco, Lister)

Every dev team should carefully evaluate modes of work with a focus on asynchronous work, especially with the trend towards remote, distributed teams which lack the physical cues of flow state.

Different contexts and modes of interactions — face-to-face meetings, Zoom calls, emails — demand different levels of focus and attention. Each of those modes have an effect on productivity.

Many of the tools meant to facilitate communication — and nominally improve productivity — can easily end up overwhelming teams by creating too much constant literal and figurative “noise”. Slack is one of the biggest offenders. A recent thread on Hacker News spawned a discussion on strategies to manage the interrupt-driven nature of a communication culture gone awry. Another titled “As a dev, Slack has ruined my life” seems a bit dramatic, but ultimately is another signal that the interrupt-driven nature of Slack is not conducive to the focused work required by software engineering teams.

One of the easiest ways to create a more productive, asynchronous work culture: focus on a written culture and write things down.

Write Things Down

What never fails to surprise me is how many misunderstandings go away when things are written down. Building software is ultimately an activity whereby a team of people codifies the ideas and visions of another team of people and one thing that is clear since the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel is that the transmission of ideas is hard.

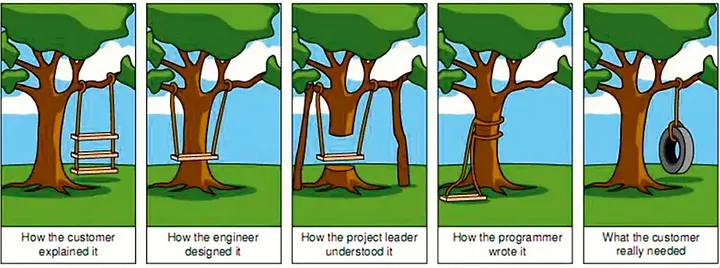

This classic is an observant take on just how difficult it is to communicate requirements:

We’ve all experienced this at some point in our career.

This classic is an observant take on just how difficult it is to communicate requirements:

We’ve all experienced this at some point in our career.

Writing things down is one of the key practices that can help teams operate more asynchronously and more productively, deliver with higher quality, and improve the end-user experience.

At InnovoCommerce, our customers were large European pharma companies who were 5 hours ahead of the US east coast and a full 8 hours ahead of our main team in PST. Early on in my tenure, I also managed and coordinated an offshore team in Vietnam 12 hours ahead of me. In this environment — and especially so in the context of life sciences — writing things down became a mechanism for keeping my sanity while coordinating development and delivery across multiple time zones (not to mention it is a critical component of GxP)!

In The Perks of a High-Documentation, Low -Meeting Work Culture, Kate Monica shares their experience at Tremendous:

Writing is critical for scaling teams because it permits an asynchronous, scalable mode of the transmission of knowledge.

Writing is critical for scaling teams because it permits an asynchronous, scalable mode of the transmission of knowledge.

Brendan O’Leary — formerly of GitLab — wrote about some of his key takeaways from his time there:

First on his list.

First on his list.

How does writing things down help?

First is that it clearly defines expectations. If there is any miscommunication, it is easy to reference and it is easy to double check. It allows people to evaluate and analyze complex concepts asynchronously perhaps when one party has more focus or more time to dedicate to the decisions or feedback at hand. There is simply far less ambiguity in the written form and far more room for structured presentation of information.

Second is that the precision and history of the written word creates accountability. Documentation is central to the FDA’s GxP guidance because it is the mechanism by which serious adverse events are traced to their origin. More generally in software, a written trail of requirements and intent is the ultimate origin of accountability. Is it a deviation? Or is it as designed? Consult the written specification!

Third is that while it requires an up-front investment, writing things down creates a long tail of velocity. Handing it off to your QA team to verify? When you’re onboarding a new resource 6 months down the line? Troubleshooting issues in production once it ships? Planning the next iteration of a feature a year later? All of it will be faster, easier, and accomplished with greater precision with the presence of written notes documenting the original requirements, decisions, assumptions, and technical details throughout the lifecycle of the software as it moves from dev to dev, team to team, test to production to sun-setting.

On a personal level, writing things down has a very practical utility as it allows me to “unload” a context and switch into another in a more streamlined way. Simon Willison wrote something in his essay Coping Strategies for the Serial Project Hoarder that really struck a chord with me:

I’m maintaining a lot of different projects at the moment. Somewhat unintuitively, the way I’m handling this is by scaling down techniques that I’ve seen working for large engineering teams spread out across multiple continents.The key trick is to ensure that every project has comprehensive documentation and automated tests. This scales my productivity horizontally, by freeing me up from needing to remember all of the details of all of the different projects I’m working on at the same time. — Simon Willison

With the complexity of modern stacks and toolsets, even writing down the details of how to setup and run a project become important!