React is the New IBM

Those of us that have been in the industry long enough have seen variations of this phrase come and go:

No one ever got fired for picking IBM

The first hit on Google has a great blog post on this:

[It] is an unattributed quote that’s been repeated so often in tech circles that it’s buried into the mindset of a lot of longtime IBM® users.And that’s a problem for progress.

It’s a status quo mindset — the biggest enemy of pure innovation.

Variants of this have come and gone; replace “IBM” with “Oracle” or “Microsoft” or “Intel” or “SAP” and you get the point.

While React obviously isn’t a company, I’d proffer that React now holds the same crown: it’s a problem for progress and a symptom of a status quo mindset.

The State of Frontend

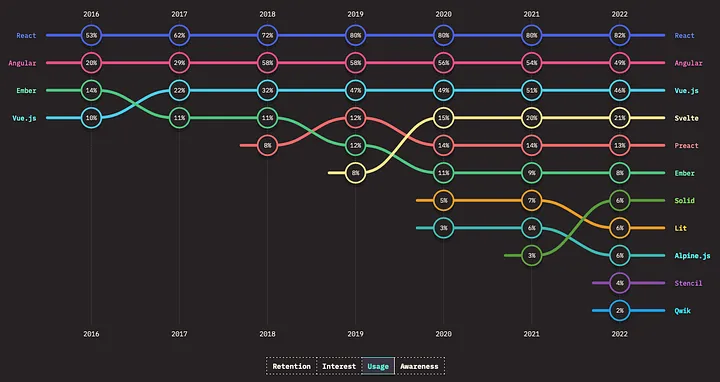

The State of JS 2022 survey unsurprisingly shows that React is still on top in terms of usage. In fact, it continues to grow in marketshare (at least in the limited audience of this survey):

Usage of React actually ticking up; likely related to Next.js growth, IMO.

Usage of React actually ticking up; likely related to Next.js growth, IMO.

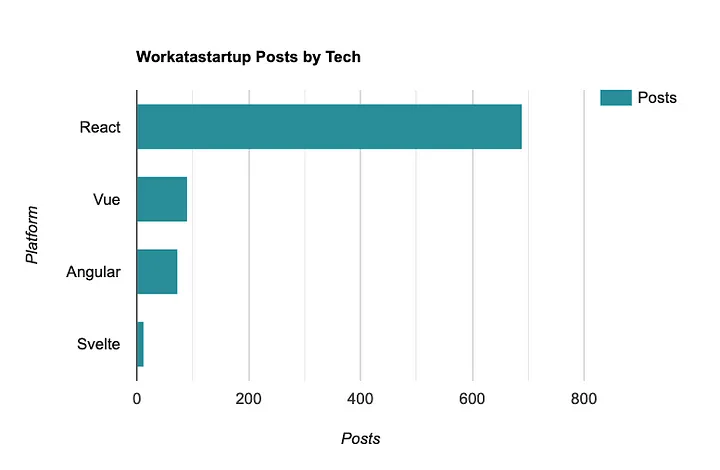

If we use YCombinator’s Work at a Startup job posting site as a proxy of the startup world, you can see that it skews even more heavily towards React:

A good proxy of the broader startup space.

A good proxy of the broader startup space.

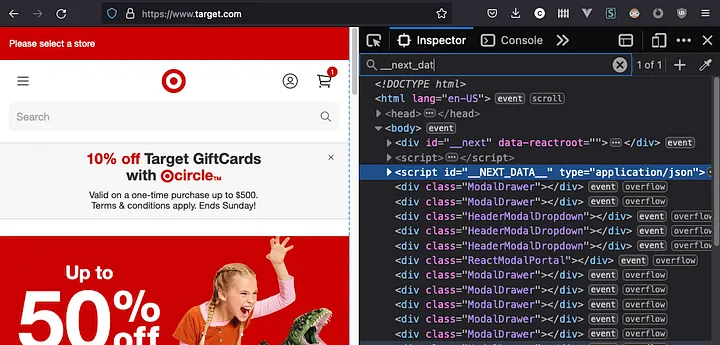

It’s even now used by major properties like Target:

Target’s dotcom with Next.js

Target’s dotcom with Next.js

And Walmart:

Walmart’s dotcom with Next.js

Walmart’s dotcom with Next.js

There’s no clearer signal that React is now the “safe” choice — the modern IBM — and that’s why you probably shouldn’t choose it.

The Problems with React

Performance

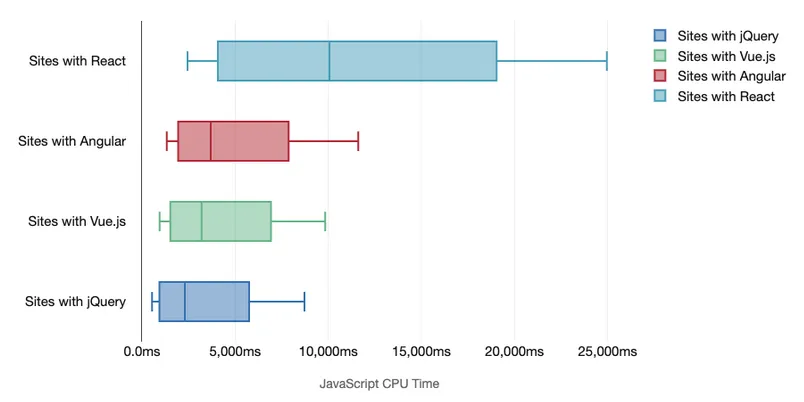

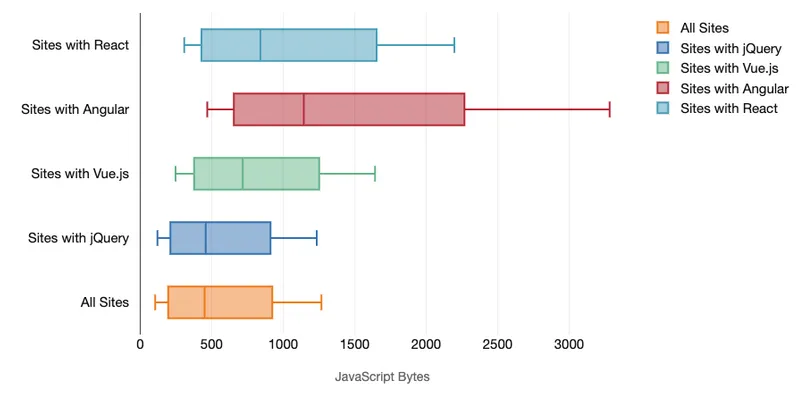

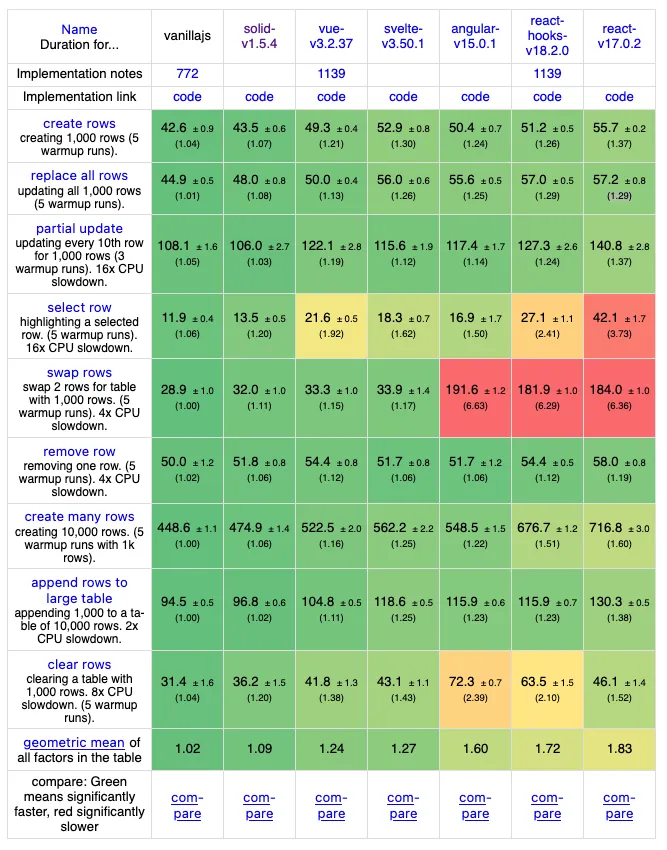

Among the major front-end libraries— React, Angular, Vue, Svelte, and Preact — React is one of the worst performing libraries.

Whether it is in terms of payload size:

Via Tim Kadlec

Via Tim Kadlec

Or CPU time:

Via Tim Kadlec

Via Tim Kadlec

React performs terribly.

Benchmarks for the major UI libraries consistently show React as a poor performer:

Execution duration

Execution duration

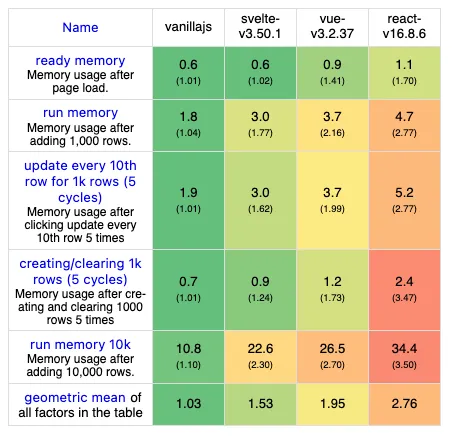

Across just about every single meaningful facet of performance:

Memory allocation

Memory allocation

React’s combination of poor payload size, poor execution speed, and high memory consumption make it a particularly poor choice for web apps that target a mobile audience.

Ecosystem vs Innovation

Despite all of this, React remains the top library for front-end development.

Part of this is that it is the by-product of a self-fulfilling prophecy not unlike the days of IBM or Microsoft’s dominance: the ecosystem and perceived “safety” of picking IBM or Microsoft or Oracle or React creates a self-feeding cycle of more React which I’ve seen expressed as:

while (react.isPopular) {

react.isPopular = true

}But this creates a blind spot: innovation.

You see: the bigger the ecosystem, the greater the dependencies, the higher the difficulty in innovating. Not just for the sake of innovating, but to improve performance, improve DX, improve the end-user experience of interacting with modern web apps. Once a faction has gained the market dominance that React has, innovation is all but guaranteed to go by the wayside.

Is it possible to be more “status quo” than this?

Is it possible to be more “status quo” than this?

When I first saw Andrew Clark’s tweet, I thought it was a joke. Surely, this was tongue-in-cheek, right?

“But I prefer React’s model where you pretend the whole thing is recreated every time”

But it’s no joke; indeed, the React team will double down on this approach despite all evidence that there are better, faster models because the team is first off constrained by its marketshare and also too arrogant to admit that they’ve been selling us — the developers and end users — lemons.

As Alex Russell writes in his opinion piece:

The market for lemons depends on customers having less information than those selling shoddy products. Some who hyped these stacks early on were earnestly ignorant, which is forgivable when recognition of error leads to changes in behaviour. But that’s not what the most popular frameworks of the last decade did.

Andrew Clark’s vision of using more compiler magic to solve for React’s shortcomings is indeed a very Facebook-esque approach to solving problems with performance and suitability of the underlying technical model. We’ve seen the same with the HipHop Virtual Machine — created to solve PHP’s issues at scale — and Hack programming language. But the compiler is fundamentally solving the wrong problem; it is a band-aid on a self-inflicted wound caused by React’s “special” model of reactivity built around the component function instead of a reactive callback:

On the one hand, I do think we should praise the React team for ensuring that teams that have invested in React don’t have to toss their efforts by starting from the ground up (much as they were able to scale poor performing PHP with HipHop). However, on the other hand, you can see that the solution to the failings of React is to stray further from progressive approaches to building web-UIs by forcing more of the “magic” into a compiler to make a broken model work.

It is clear to me that React is a dead-end and its fundamental failings can only be “solved” by compiler magic slapping band-aids labeled useMemo and useCallback into the transpiled output. We’re building JavaScript and HTML front-ends here, not operating systems!

Complexity

Like IBM mainframe systems of the old days and Microsoft’s enterprise software, the complexity of such systems is highly undersold. That’s part of the power of being in a dominant position and being the “safe” choice: the marketshare creates an illusion.

Once again, Alex Russell’s essay puts it bluntly:

The complexity merchants knew their environments weren’t typical, but they sold highly specialised tools as though they were generally appropriate. They understood that most websites lack tight latency budgeting, dedicated performance teams, hawkish management reviews, ship gates to prevent regressions, and end-to-end measurements of critical user journeys. They understood the only way to scale JS-driven frontends are massive investments in controlling complexity, but warned none of their customers.They could have copped to an honest error, admitted that these technologies require vast infrastructure to operate; that they are unscalable in the hands of all but the most sophisticated teams. They did the opposite, doubling down, breathlessly announcing vapourware year after year to forestall critical thinking about fundamental design flaws. They also worked behind the scenes to marginalise those who pointed out the disturbing results and extraordinary costs.

React’s complexity is well hidden but is inherent in the render cycle’s assumption of stateless components which means that developers need to understand when and where to carefully place state.

React’s functional model makes certain assumptions about the difficulty of managing state which I think simply aren’t true. World of BS has a nice, concise writeup on different programming philosophies and how they view state:

I recently realized that all the various programming philosophies are concerned with state, and can be boiled down into a simple statement about how to work with state.Object-Oriented — Modifying a lot of state at once is hard to get correct; encapsulate subsets of state into separate objects and allow limited manipulation of the encapsulated sub-state via methods.

Functional — Modifying state is hard to get correct; keep it at the boundaries and keep logic pure so that it is easier to verify the logic is correct.

So does React’s functional approach reduce the complexity of getting state correct?

If you’ve found yourself going back to your code after finding an errant side effect and adding in useMemo and useCallback after finding a weird bug in your UI, then welcome to the club. React’s render model and insistence on functional purity is counterintuitive when considering how every stateful UI application library or framework — whether it’s desktop apps, mobile apps, 3D game libraries, etc. — is designed.

Yes, at a low-level, a graphics card will draw frame-by-frame discarding the buffer of pixels that came before, but that is a low-level implementation detail and abstractions mean that such low level details do not bubble to the developer where we generally always assume that our component or object is stateful. In other words, the purpose of an engine like Unreal or Unity or Godot is to improve productivity through abstractions.

Perhaps there’s a reason for Facebook to ask that React developers pretend that the DOM tree is recreated each time (when in fact, it is not) 🤷♂️.

This gets me to my next point:

It Doesn’t Solve Your Problem

I admit, React’s initial learning curve is incredibly low as React itself is primarily concerned with simply rendering and the barest of state management. Even if you do React poorly (e.g. not writing “pure”, side-effect free components), you rarely notice the issues.

Yet React’s logical model of recreating the UI on change of state is incredibly difficult to do right at scale. By that I mean that as applications and teams get larger, the chances of writing components with side effects increases due to differing levels of skill, knowledge, experience, and simply having a larger body of code to cover.

For Facebook and large enterprise teams like Target and Walmart, this may be manageable through rigorous testing, additional tooling, and better training. The question here then is whether React is the best tool for a startup or a small team that wants to move at speed. I posit that the answer is “No”; React was born out of Facebook to solve Facebook’s problems at Facebook’s scale with Facebook’s resources.

In some sense, this recalls Scott Carey’s article Complexity is Killing Software Developers which had this great qoute:

“Essential is the complexity in the business domain you are working in, the fact that enterprises are extremely complicated environments, so the problems they are trying to solve are inherently complex. The other area is accidental; this is the complexity that comes with our tooling and what we layer on top when solving a problem.”

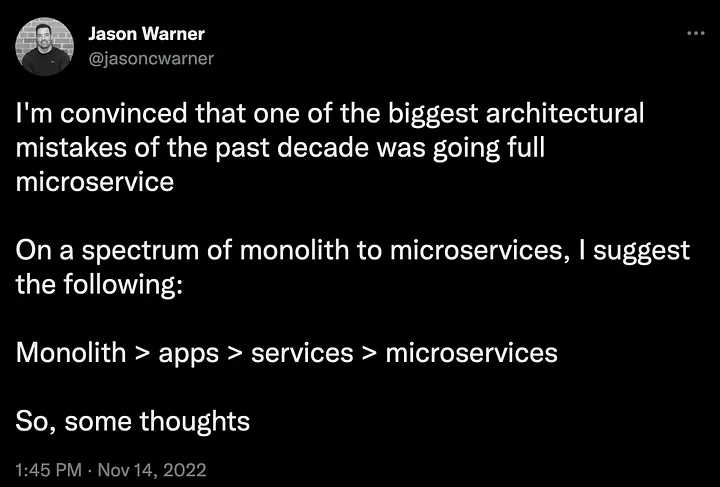

In particular, Carey calls out the shift from monolithic approaches to microservices as one of the key sources of complexity in modern architectures.

There is certainly a place and a time for microservices and the added level of complexity that comes along with it, but the question that every team needs to ask themselves is “Do I need this?”.

Jason Warner — former GitHub CTO’s thoughts on microservices.

Jason Warner — former GitHub CTO’s thoughts on microservices.

Like the complexity of React, the answer is probably “No”; the majority of us are not solving Facebook or Target or Walmart scale problems with Facebook or Target or Walmart scale resources with the option to use Facebook or Target or Walmart level hacks and workarounds.

For the rest of us — especially startups — being able to move fast without foot-gunning ourselves is probably the more important facet of selecting a tech stack.

Much of the innovation in the UI space is now happening around the edges of the React ecosystem: Solid.js, Preact.js, Svelte.js, Vue.js, Astro.js, Qwik.js, Marko.js, and progressive enhancements using modern JavaScript capabilities.

Like IBM, React will one day lose its crown by virtue of its own mass and inability to innovate towards better solutions. It is already apparent in how the team thinks about the state of front-end and how to continue to (not) improve the experience for developers, teams, and end-users. While Evan You of Vue has no problems borrowing better ideas from other teams (e.g. Vue’s upcoming Vapor mode), the React team simply doubles down despite acknowledging that there are better models for performance; it’s difficult to stop selling lemons when lemons are all you’ve got!

React is the new IBM: you should learn it, you should understand its faults, you should probably still deploy it. You’ll never get fired for picking it, but it’s going to be expensive, bloated, difficult to get right, and it’s going to be joyless implementing it every step of the way. React is “the status quo mindset — the biggest enemy of pure innovation”.