Server Sent Events with .NET 7

What are Server Sent Events

Server Sent Event (SSE) is a mechanism for a server to stream data to the browser and then surface those messages as events.

If you’ve used any of the AI chat tools, you’ve probably seen it in action.

In practice, it can be a good alternative to options such as WebSockets when you need to have specific windows of server-pushed events since it’s easy to implement as just another HTTP endpoint in your API without much added complexity.

We’ll take a look at how to implement this using .NET 7 web APIs.

💡 Full repo is available here GitHub: CharlieDigital/dn7-server-sent-events

Create the API

Start by creating a simple .NET web API:

mkdir dn7-sse

cd dn7-sse

dotnet new webapi -minimalWe’ll need to add some basic setup:

// Add CORS so our front-end can access it.

builder.Services.AddCors();

// Add the HTTP context accessor into dependency injection

builder.Services.AddHttpContextAccessor();Then we’ll need to set our CORS policy:

app.UseCors(policy => policy

.AllowAnyHeader()

.AllowAnyMethod()

.WithOrigins(

"http://localhost:5173"

));The SSE endpoint itself is quite simple:

var SSE_CONTENT_TYPE = "text/event-stream";

var LINE_END = $"{Environment.NewLine}{Environment.NewLine}";

app.MapGet("/sse", async (

IHttpContextAccessor accessor,

CancellationToken cancellation

) => {

var response = accessor.HttpContext!.Response;

response.Headers.Add(HeaderNames.ContentType, SSE_CONTENT_TYPE);

while (!cancellation.IsCancellationRequested) {

await foreach (var segment in GenerateTextStreamAsync()) {

await response.WriteAsync($"data: {segment}{LINE_END}", cancellation);

await response.Body.FlushAsync(cancellation);

}

break; // We've written all of the text.

}

await response.WriteAsync($"data: [END]{LINE_END}", cancellation);

await response.Body.FlushAsync(cancellation);

});We iterate over our (simulated) content stream and write it segment by segment. In this case, we’re simply returning a stream of text from Lorem Ipsum, but it need not be so simple. The code could use Task.Delay and then query a database, for example, for new events to stream back to the caller.

Each event is delineated by a double newline and we use a custom event payload [END] to tell the client side that the stream has completed.

Implement the Client

The client implementation relies on the EventSource. In this example, we’re just using some simple vanilla JS:

const $ = (selector) => document.getElementById(selector);

async function generate() {

$("passage").innerText = "";

$("generate").disabled = true;

$("reset").disabled = false;

const evtSrc = new EventSource("http://localhost:5081/sse");

evtSrc.onmessage = (evt) => {

// Received our [END] payload so we know this is the end of the stream.

if (evt.data.trim() === "[END]") {

evtSrc.close();

$("generate").disabled = false

return;

}

// Otherwise, append the payload to the <p>

$("passage").innerText += ` ${evt.data}`;

}

}On each message (double newline), we check to see if we’ve reached the end of our stream by checking for [END]. If not, we just keep appending the text.

Easy!

Keep in mind that you can send back any payload that you want: JSON, XML, bytes - whatever suits your needs.

Special Considerations

There are three “gotchas” to be aware of:

Supporting POST and Request Headers

The EventSource interface is notably sparse. If you need to send information upstream to the API via a POST or headers (e.g. auth headers), you’ll need a library like @microsoft/fetch-event-source. There are a few that you can use, but they are effectively replacements for the native EventSource.

Handling Client Disconnect

In the event that the client disconnects, we ideally want the server to immediately stop processing. To achieve this, you’ll notice that the async calls all forward the CancellationToken so that they can interrupt the flow if the client disconnects.

One notable issue with this is that it will generate an unhandled exception on the .NET side every time this happens.

To mitigate this, we can add a middleware to handle this exception:

app.UseMiddleware<OperationCanceledMiddleware>();

public class OperationCanceledMiddleware {

private readonly RequestDelegate _next;

public OperationCanceledMiddleware(RequestDelegate next) {

_next = next;

}

public async Task InvokeAsync(HttpContext context) {

try {

await _next(context);

} catch (OperationCanceledException) {

Console.WriteLine("Client closed connection.");

}

}

}Now instead of an exception stack in the log output, we’ll simply have a Client closed connection or we can ignore it.

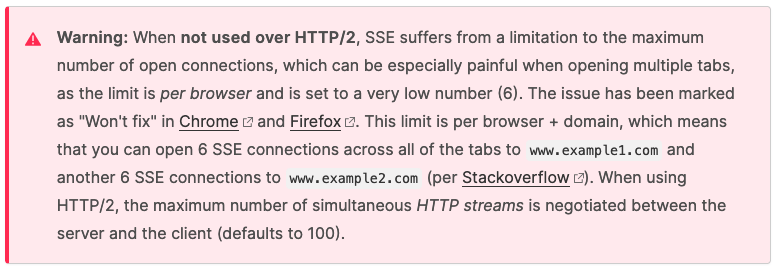

HTTP/2 versus HTTP/1

When using HTTP/1 from the server, the client is limited to only 6 connections for the entire browser + domain:

You’ll want to ensure that you have HTTP/2 enabled on the server.

To do so for Kestrel, you can add the following into your appsettings.*.json (assuming you only need it for your upstream environments):

{

"Kestrel": {

"EndpointDefaults": {

"Protocols": "Http2"

}

}

}If you’re running this in Google Cloud Run, don’t forget to enable HTTP/2!

Conclusion

Server Sent Events are a useful tool to have in your belt for building certain types of streaming interactions from the server to the client. It’s an alternative to web sockets when you’d prefer to have an HTTP based solution and there is a bias to the server response stream pushing events rather than the client request stream pushing events.

Because it’s “just HTTP”, the result is that its easy to monitor, easy to debug, easy to implement, and has predictable scalability concerns in terms of your network and backend infrastructure.

If you made it this far, add this RSS feed to your blog reader of choice or tag me on Mastodon @chrlschn or X @chrlschn.