TypeScript is not a Programming Language

A Mastodon post got me thinking about TypeScript and why some developers end up throwing their hands up when adopting it.

My conclusion is that it starts at the very name: “TypeScript” and a misconception that it is simply statically typed JavaScript.

It is not.

TypeScript is not a statically typed programming language; TypeScript is JavaScript with shape definitions.

In reality, it’s probably easier to not think about TypeScript as a programming language or even as a type system. Perhaps the easiest way to wrap your head around TypeScript is to think of it as a shape definition markup.

Rethinking Type as Shape

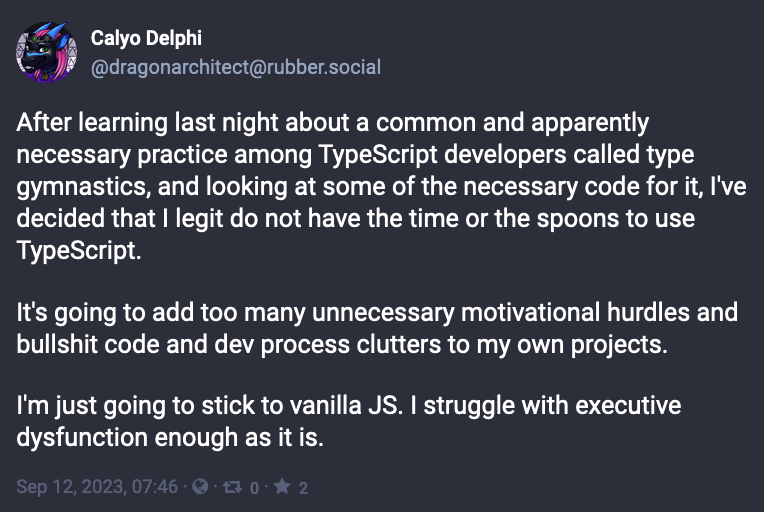

A simple example to highlight this is the following code snippet:

type Req = {

uid: string

operation: string

}

interface Req2 {

uid: string

operation: string,

archive: () => void

}

function process(req: { uid: string, operation: string }) {

console.log(`${req.uid} ${req.operation}`)

}

const r1 = {

uid: 'r1',

operation: 'add'

}

const r2: Req = {

uid: 'r2',

operation: 'add'

}

const r3: Req2 = {

uid: 'r3',

operation: 'add',

archive: () => console.log('Archived!')

}

process(r1)

process(r2)

process(r3)On line 12, we describe the shape of the parameter req to the function process.

When we run this code, we can see that it behaves precisely as expected:

What should be apparent looking at the function definition on line 12 is that TypeScript is not a static type system; it’s actually a shape definition system (or more formally, a structural type system, but it’s easier if you think of it as describing valid shapes).

And if we peek at the JavaScript:

"use strict";

function process(req) {

console.log(`${req.uid} ${req.operation}`);

}

const r1 = {

uid: 'r1',

operation: 'add'

};

const r2 = {

uid: 'r2',

operation: 'add'

};

const r3 = {

uid: 'r3',

operation: 'add',

archive: () => console.log('Archived!')

};

process(r1);

process(r2);

process(r3);It’s pretty clear why this works. You can see that in the output JavaScript, the TypeScript disappears. This is because the sole purpose of TypeScript is to inform the compiler and dev time language server about the valid shapes. In fact, neither Node nor the browser run TypeScript; they only interpret JavaScript.

(We’ll revisit this at the end)

TypeScript is Still Duck-Typed

If it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it is a duck.

A variant of the code snippet above may help further highlight this:

Note the subtle change on line 12: we describe the function as requiring a parameter req that is shaped like the type Req but the function will happily accept an object of the interface Req2 precisely because TypeScript is not a static type system. In a statically typed language like C#, this will fail because the type metadata does not match, even though the shapes match (we can still achieve this in statically typed languages like C# and Java by defining type contracts like an interface or abstract base class).

With this in mind, then many of the other utility types and odd “type gymnastics” makes sense: they’re all simply ways of describing shapes — often in the context of other, existing shapes.

TypeScript Utility Functions

To further emphasize this point, consider the following example which uses the utility type Omit<>:

type Req = {

uid: string

operation: string,

callback: string // Add this into the shape

}

interface Req2 {

uid: string

operation: string,

archive: () => void

}

function process(

req: Omit<Req, "callback"> // Exclude it in our shape constraint

) {

console.log(`${req.uid} ${req.operation}`)

}

const r1 = {

uid: 'r1',

operation: 'add'

}

const r2: Req = {

uid: 'r2',

operation: 'add',

callback: "https://example.com/callback"

}

const r3: Req2 = {

uid: 'r3',

operation: 'add',

archive: () => console.log('Archived!')

}

process(r1)

process(r2)

process(r3)Or alternatively, the inverse using the utility type Pick<>:

function process(

req: Pick<Req, "uid" | "operation"> // Explicit shape definition

) {

console.log(`${req.uid} ${req.operation}`)

}Each is simply a different way of describing the valid shapes. Pick<> and Omit<> are simply ways for us to derive a different shape from an existing shape.

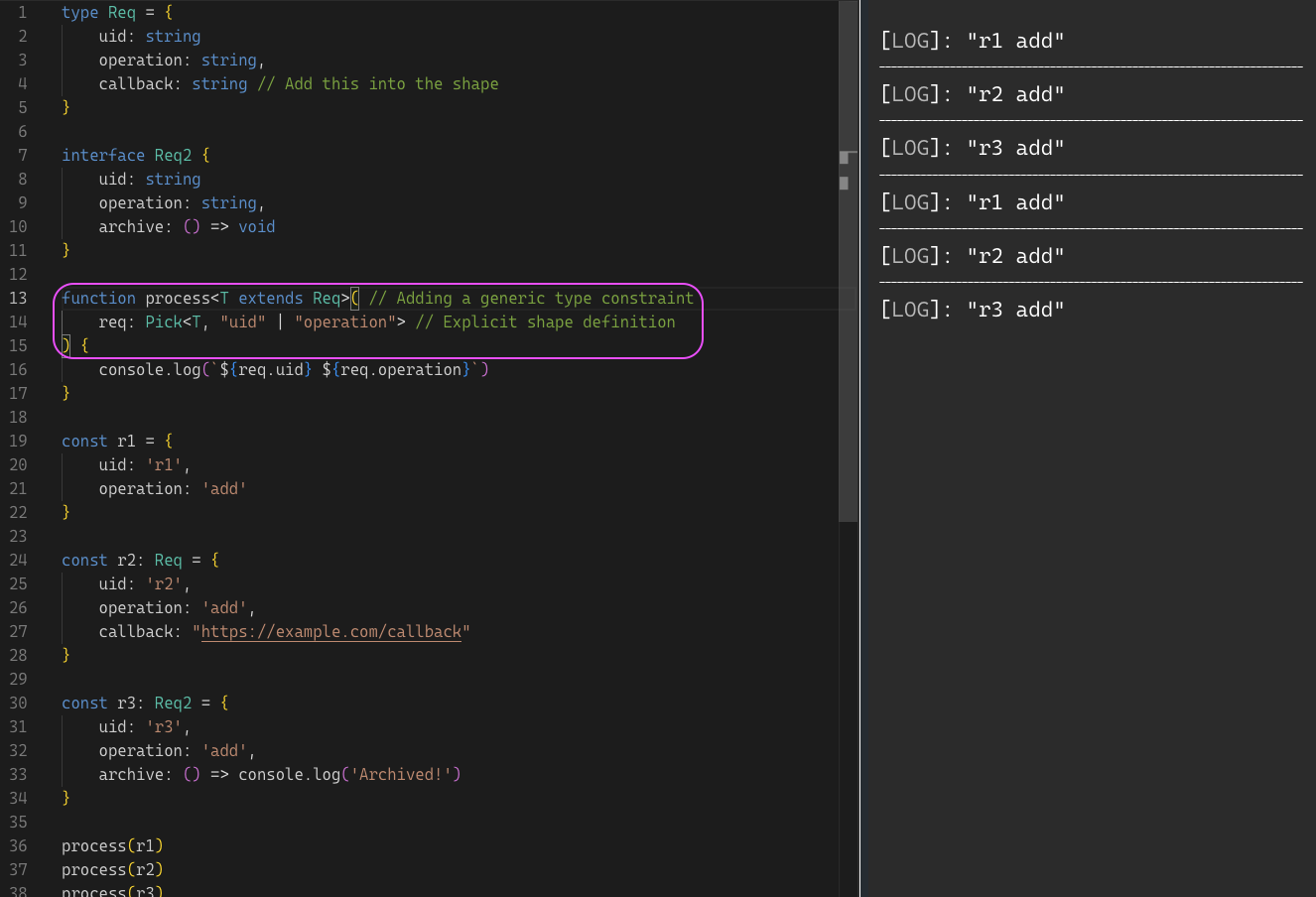

TypeScript Generics

Even if we add a generic type constraint (line 13):

It works all the same because we haven’t changed the resultant shape — just how we describe that shape.

Intersection Types

Even this construct using intersection types is OK:

type Identifiable = {

uid: string

}

type Instruction = {

operation: string,

params: string[]

}

type Req = {

uid: string

operation: string,

callback: string // Add this into the shape

}

interface Req2 {

uid: string

operation: string,

archive: () => void

}

function process<T extends Identifiable & Instruction>( // Defining the shape using an intersection type

req: Pick<T, "uid" | "operation"> // Explicit shape definition

) {

console.log(`${req.uid} ${req.operation}`)

}TypeScript happily accepts it all because our shapes still match.

There is no Spoon Type

Remember that JavaScript we saw earlier?

// TypeScript

function process(req: Req) {

console.log(`${req.uid} ${req.operation}`)

if ( /* req is Req type */ ) { // ❌

// Do Req specific thing

} else {

// Do other thing

}

}

// Transpiled JavaScript doesn't make sense

function process(req) {

console.log(`${req.uid} ${req.operation}`);

if ( /* ??? */ ) {

// Do Req specific thing

} else {

// Do other thing

}

}One of the most common misunderstandings that arises is when developers want to perform different branching logic based on the type in the TypeScript code. Because the resultant JavaScript carries no actual type metadata, this simply doesn’t work. It is often confusing for developers coming from statically typed language systems like C# where it does work.

The reason this is worth highlighting is to really emphasize the purpose of TypeScript: to inform the dev time language server and the compiler about the valid shapes — nothing more.

Conclusion

If you’re a developer throwing your hands up with TypeScript, the first thing to do is to probably ignore the “Type” part of the name and perhaps think of it as “ShapeDef” 🤣; you’re describing the valid shapes to the language server at dev time, the compiler at compile time, and for the sanity of your fellow dev team. TypeScript is not a statically typed programming language; TypeScript is JavaScript with shape definitions.

The second thing to do is to pick up Adam Freeman’s Essential TypeScript book (not an affiliate link; it’s just a great book). This is hands down one of the best technical books I have in my possession and a great book for any developer that wants to do TypeScript well.

What I hope is clear from these short examples is that thinking of TypeScript as a programming language or as a static type system will ultimately create a mental hurdle to understanding how to use this shape definition system to write safer JavaScript.