A Conceptual Model of State in Vue 3.4

Summary

Getting state and componentization right in the frontend remains one of the biggest challenges as modern web applications increase in complexity. The defineModel macro released with Vue 3.4 provides a streamlined way to think about how to model complex, inter-component state management that still retains strong locality and compartmentalization of data

The full sample code is in this GitHub Repo: https://github.com/CharlieDigital/vue3-state-definemodel

Intro

Understanding placement of state and component boundaries remains one of the major challenges in modern frontend web development and is often one of the most important decisions teams can make that can either accelerate development as the scale of an application increases or become the biggest source of friction.

When done right, it makes building, composing, refactoring, and testing frontend components a breeze. When done poorly, it can be the endless source of phantom bugs that can be difficult to trace and make the codebase feel fragile.

The defineModel macro — released from its experimental status with Vue’s 3.4 release — is perhaps one of the more game-changing features when it comes to how it can shape the way teams think about and implement complex state interactions between different components.

The description seems quite innocuous:

defineModelis a new<script setup>macro that aims to simplify the implementation of components that support v-model

On the surface, this macro’s utility seems subtle, but it has a profound effect on how teams can think about state and managing component boundaries. Let’s take a look at what defineModel does and why its addition in Vue 3.4 feels like a paradigm shift — even though it’s just a simple macro.

Frontend State Models at a Glance

In general, there are 3 scopes of state when we think about modern frontend applications (excluding window level truly global state).

- Global, shared state. This is state that is accessible across different components within the entire hierarchy for truly global state like the logged in user account information and information shared between routes.

- Hierarchical component state. This is state that is accessible across different components within a subtree of the hierarchy. Examples are a listing-detail editor view.

- Single component level state. This is state that is accessible only within a single component within a hierarchy and does not leave the boundary of the component as state interactions do not need to go up or down the tree.

At the global level, there are many libraries and solutions for solving this. For example, React’s Zustand, Jotai, Recoil, Redux (among others) and Vue’s Pinia help pull state out from the component tree into a global scope to cut across the tree. It’s intended to hold truly global state like light/dark mode or tenant ID’s.

This second layer of state is where teams encounter the friction of “prop drilling” — whether in React, Vue, or other libraries or frameworks. Part of it is that it is onerous to manage moving state up and down this tree between components.

The natural decision teams make in this case is to move state out into a global store or fall into the third component scope of state and simply keep piling into one massive component to avoid that friction — creating another kind of pain instead.

Wouldn’t it be nice if it were easy to separate state without the friction and pain of prop drilling while maintaining Vue’s reactive two way binding? This is precisely where defineModel comes into play as it dramatically reduces the friction of moving state between components in a tree while maintaining Vue’s two way binding.

What is defineModel?

It’s important to first understand what it is and what it does. For those unfamiliar with Vue, the idiomatic model of moving state up and down between components uses the pair of props and emits.

Before defineModel - props and emits

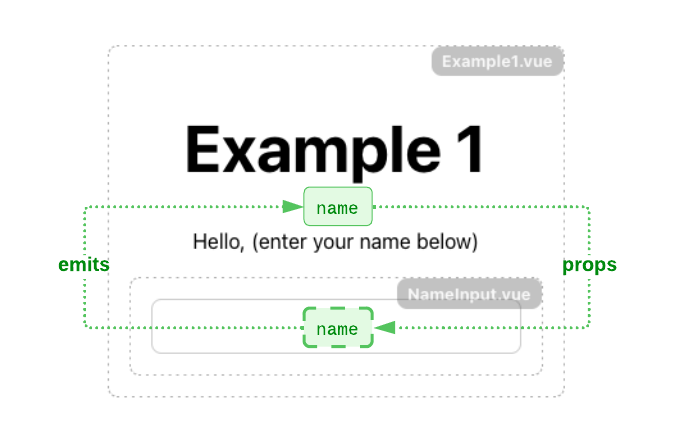

For example, consider this parent-child component:

The outer component defines the ref which gets passed down into the child as a prop. The update occurs through an emit from the child to the parent

The outer component defines the ref which gets passed down into the child as a prop. The update occurs through an emit from the child to the parent

To get the two way binding, we need the inner NameInput.vue component to look like this:

<!-- NameInput.vue -->

<template>

<LabeledContainer label="NameInput.vue">

<!-- 👇 Bind it here to our input -->

<input v-model="name"/>

</LabeledContainer>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

// 👇 Enters as a prop

const props = defineProps<{

modelValue: string

}>()

// 👇 Emit the update to the parent

const emits = defineEmits<{

'update:modelValue': [string]

}>()

// 👇 A writable computed to tie it together.

const name = computed({

get() {

return props.modelValue

},

set(val) {

emits('update:modelValue', val)

}

})

</script>And the outer Example1.vue component:

<!-- Example1.vue -->

<template>

<LabeledContainer label="Example1.vue">

<h1>Example 1</h1>

<p>Hello, {{ name.length === 0 ? "(enter your name below)" : name }}</p>

<!-- 👇 Here is our component -->

<NameInput v-model="name"/>

</LabeledContainer>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

const name = ref('')

</script>Now when we type a value into the text box, this automatically updates the value of the prop:

It’s easy to see how this boilerplate can become tedious!

After defineModel ✨

With the release of defineModel in Vue 3.4, let’s look at how this simplifies NameInput.vue:

<!-- NameInput.vue -->

<template>

<LabeledContainer label="NameInput.vue">

<input v-model="name"/>

</LabeledContainer>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

// 🎉 Just a single line!

const name = defineModel<string>({ required: true })

</script>The parent component remains unchanged, but a large volume of boilerplate code has been removed! This tiny macro completely changes the ergonomics of managing state.

A Practical Example

On the surface, this seems quite a trivial change. Sure, some convenience has been gained, but how does this really affect how developers manage state? Isn’t it preposterous to claim so when it’s just a simple macro?

The reality is that developers tend to take the path of least resistance and if the path of least resistance is one of bad practices then, well, developers will create a codebase with many, many bad practices — AKA “Tech Debt”. If you’ve seen a 1000+ line React or Vue component (and who among us hasn’t?), then the likely reason is that there was simply too much friction in parceling out the state in a manageable way as the component grew organically; it was easier to just keep sharing the same state in one massive component than to break out a new component.

What defineModel accomplishes is that it creates a path of least resistance that also happens to help improve how teams can think about state. Suddenly, that middle ground of managing hierarchical component state becomes trivially easy and removes the temptation to move state into a global scope or take the lazy route and resist breaking large components into smaller components because shuttling state up and down is painful (how 1000+ line components typically come to be).

Using defineModel to Simplify Hierarchical State

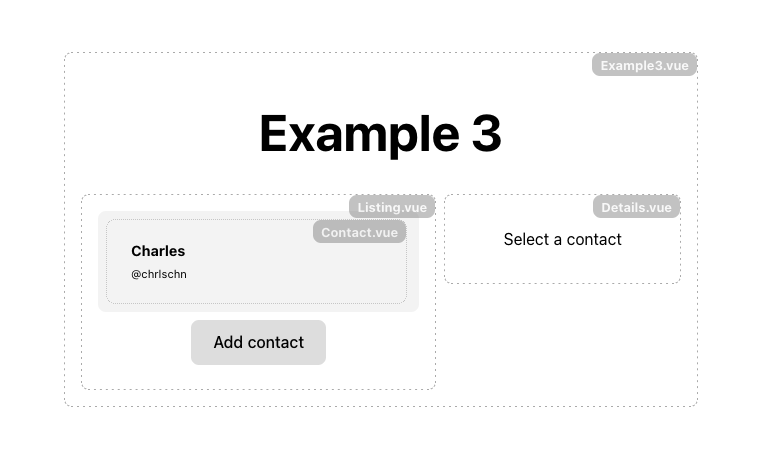

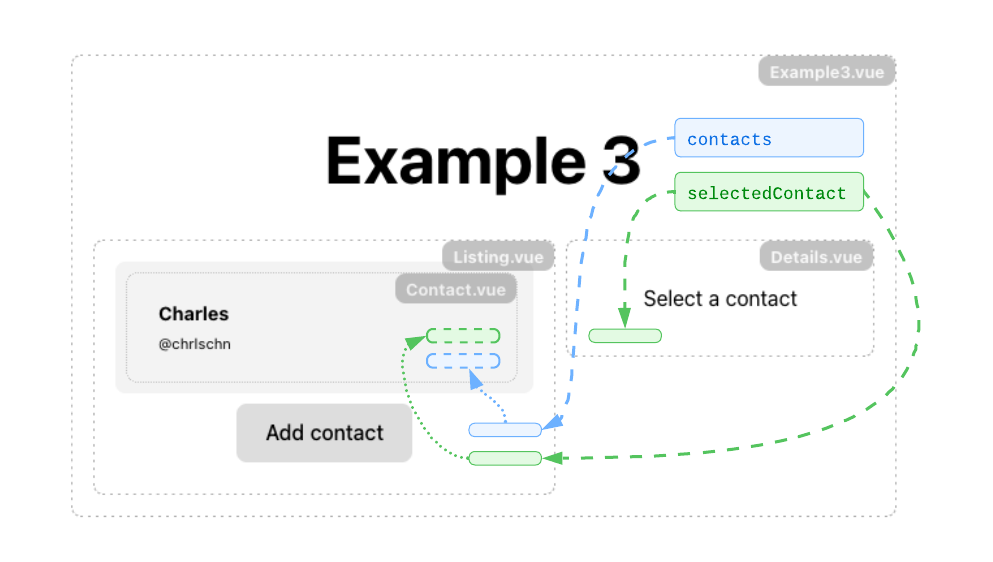

Consider the following simple contact management app:

Note the hierarchy of components and the two clear subtrees.

Note the hierarchy of components and the two clear subtrees.

Take note of the hierarchy in this example. When a user selects a contact from Listing.vue, the app should show the details in Details.vue. When the user edits the details and save the changes in Details.vue, the app should update the entry in Listing.vue.

If we want to share state between Listing.vue and Details.vue, it has to either be global state or hierarchical state that starts from the common parent Example3.vue — otherwise, it’s easy to see the temptation to glob everything into one massive component!

In this case, this is what our hierarchical state looks like:

The distribution of state into the contact component is via a prop from the listing

The distribution of state into the contact component is via a prop from the listing

Let’s examine the code from the outside in.

Here is our parent Example3.vue component:

<template>

<LabeledContainer label="Example3.vue">

<h1>Example 3</h1>

<p v-if="!!selectedContact">

Selected: {{ selectedContact.name }} ({{ selectedContact.handle }})

</p>

<div class="parent">

<!-- 👈 Left branch -->

<Listing

v-model="contacts"

v-model:selected="selectedContact"/>

<!-- 👉 Right branch -->

<Details v-model="selectedContact"/>

</div>

</LabeledContainer>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

const selectedContact = ref<Contact>()

const contacts = ref<Contact[]>([{

name: 'Charles',

handle: '@chrlschn'

}])

</script>This is the root where our state lives and we pass it down via bindings to the Listing and Details components:

<!-- Snippet from Example3.vue-->

<Listing

v-model="contacts"

v-model:selected="selectedContact"/>

<Details v-model="selectedContact"/>Let’s look at Details.vue first:

<!-- Details.vue, the right side form inputs -->

<template>

<LabeledContainer label="Details.vue">

<div v-if="!!selected">

<!-- Input for the user name -->

<label>

Name

<input v-model="name"/>

</label>

<!-- Input for the user handle -->

<label>

Handle

<input v-model="handle"/>

</label>

<!-- Action buttons -->

<div>

<button @click="handleCancel">Done</button>

<button @click="handleDone">Save</button>

</div>

</div>

<p v-else>

Select a contact

</p>

</LabeledContainer>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

const selected = defineModel<Contact|undefined>({

required: true

})

const name = ref('')

const handle = ref('')

// When the selected value updates, we update our local copy.

watch (selected, (contact) => {

if (!contact) {

return

}

name.value = contact.name,

handle.value = contact.handle

})

// If changes are cancelled, we revert everything.

function handleCancel() {

selected.value = undefined

}

// If changes are saved, we update the selected object.

function handleDone() {

if (!selected.value) {

return

}

selected.value.name = name.value;

selected.value.handle = handle.value;

}

</script>This component has been written with the intent of having a set of state that gets a copy of the contact details. When the selected contact changes, the component copies the values into the local state so that it can mutate the state (name and handle) without affecting the original until the user saves. With this, the user can also cancel any edits as well.

(For larger sets of properties, consider making a full reactive copy of the object and bind directly to it instead.)

On the left hand side, the Listing.vue component contains a list of the contacts with the option to add a new one.

<!-- Listing.vue -->

<template>

<LabeledContainer label="Listing.vue">

<div class="container">

<ContactItem

v-for="contact in contacts"

:contact="contact"

:selected="selected == contact"

@click="selected = contact">

</ContactItem>

</div>

<div>

<button @click="handleAddContact"> Add contact </button>

</div>

</LabeledContainer>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

const contacts = defineModel<Contact[]>({

required: true

})

const selected = defineModel<Contact|undefined>('selected', {

required: true

})

function handleAddContact() {

contacts.value.push({

name: 'Name',

handle: 'Handle'

})

}

</script>And then in ContactItem.vue, Listing.vue passes down the display values using normal props since there is no mutation here (and no need for two way binding):

<template>

<LabeledContainer

label="Contact.vue"

class="contact"

:class="{

'selected': !!selected

}">

<p class="name">{{ contact.name }}</p>

<p class="handle">{{ contact.handle }}</p>

</LabeledContainer>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

defineProps<{

contact: Contact,

selected?: boolean

}>()

</script>Let’s see how this whole thing comes together:

Our components in action, sharing state within the hierarchy of our example component tree.

Our components in action, sharing state within the hierarchy of our example component tree.

Without defineModel to help simplify this interaction, it is easy to see how the instinct would be to take shortcuts or move this into global state since writing the various emits and computed would create quite a bit of friction, even in this small example!

As Billy Mays might say, ”But wait! There’s more!”; let’s take a look how it is possible to further make this code easier to understand and more manageable by using composables.

Using defineModel with Composables

Leveraging composables can take this to the next level and further simplify our code by pulling out our state from the components. This can be particularly useful to do when components become larger.

In Vue, this is easy to accomplish and makes refactoring and reorganizing complexity a breeze.

We simply pull our state and functions up and out of the components into another function:

// useContacts composable

export function useContacts() {

const selectedContact = ref<Contact>()

const contacts = ref<Contact[]>([{

name: 'Charles',

handle: '@chrlschn'

}])

function addContact() {

contacts.value.push({

name: 'Name',

handle: 'Handle'

})

}

return {

selectedContact,

contacts,

addContact

}

}A refactored Example3.vue → Example4.vue using the composables:

<!-- Example4.vue -->

<template>

<LabeledContainer label="Example4.vue">

<h1>Example 4</h1>

<p v-if="!!selectedContact">

Selected: {{ selectedContact.name }} ({{ selectedContact.handle }})

</p>

<div class="parent">

<Listing

v-model="contacts"

v-model:selected="selectedContact"

:add="addContact"/>

<Details v-model="selectedContact"/>

</div>

</LabeledContainer>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

// We get all of our key state from the composables instead.

const {

selectedContact,

contacts,

addContact

} = useContacts()

</script>It’s easy to see if we wanted to move more of the logic and state out from Details.vue, for example, it would be very low friction to move the name and handle refs as well as the handleCancel() and handleDone() functions into another composable and share them:

// useDetailsEditor.ts

// 👇 Note how we receive the reactive selectedContact here so we can watch it.

export function useDetailsEditor(selectedContact: Ref<Contact|undefined>) {

const name = ref('')

const handle = ref('')

// 👇 We add a watcher here on selectedContact so we update the encapsulated state.

watch (selectedContact, (contact) => {

if (!contact) {

return

}

name.value = contact.name,

handle.value = contact.handle

})

function cancel() {

selectedContact.value = undefined

}

function done() {

if (!selectedContact.value) {

return

}

selectedContact.value.name = name.value;

selectedContact.value.handle = handle.value;

}

return {

name,

handle,

cancel,

done

}

}And we update Details.vue:

<template>

<LabeledContainer label="Details.vue">

<div v-if="!!selected">

<div>

<label>

Name

<input v-model="name"/>

</label>

</div>

<div>

<label>

Handle

<input v-model="handle"/>

</label>

</div>

<div>

<button @click="cancel">Done</button>

<button @click="done">Save</button>

</div>

</div>

<p v-else>

Select a contact

</p>

</LabeledContainer>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

const selected = defineModel<Contact|undefined>({

required: true

})

const {

name,

handle,

cancel,

done

} = useDetailsEditor(selected)

// 👆 Here we pass in the selected contact so we can watch it in the composable

</script>This works nicely to cleanly separate and encapsulate related state and logic by using Vue 3 composables and Vue 3.4’s defineModel macro. What I hope is clear is just how easy it is to refactor code to this pattern by simply copying out state, functions, watchers, and computed values wholesale and pasting them into a composable.

This pattern can make even large sub-trees of components easy to manage, refactor, and test.

Closing Thoughts

The introduction of defineModel in Vue 3.4 is actually a profound change that will help teams to follow best practices and build better, more manageable components. By removing a lot of the friction involved in building hierarchical state, it makes it so that teams are less likely to resort immediately to global state or fall back to sloppy practices.

By combining defineModel with Vue composables, teams can create even cleaner components that are easy to read and understand by organizing and encapsulating related state and logic.

When Evan You first proposed the Composition API for Vue 3, there was much consternation and outcry from the community that wanted to retain the simplicity and approachability of the Options API. In retrospect, it is clear to see that the path Evan You set to help Vue scale better for teams building larger projects was the right call.

With 3.4, it feels as if that vision now feels far more complete because of how streamlined and straightforward it makes state management. In a way, it helps add clarity to the often complex decision making process of where to place state by making the easy, obvious choice the right one. defineModel feels like a small stone, cast into the ocean, who’s ripple could one day become a crashing wave!