The Inverted Reactivity Model of React

Summary

- Compared to almost every other FE framework, including Vanilla JS, React has an "inverted" model of reactivity

- In React, the component function is the unit of reactivity whereas in Vue and Vanilla JS, the callback function is typically the unit of reactivity

- Understanding this difference is important regardless of which direction you're headed (React to Vue or vice versa)

- For React developers heading into Vue, this can often reduce the mental burden when writing complex components by reducing the need to explicitly think about code placement, avoiding excess allocations (explicit memoization), and unintended side effects.

Intro

In the r/vuejs sub, there are occasionally questions from React devs wondering how to prepare for a transition to Vue (rare, but it happens! More often, it's going the other way; this topic is important both ways!).

While there are obviously a great many differences syntactically, I actually think that one of the most important things for React developers to understand about Vue -- and almost every other reactivity model, including Vanilla JS as well -- is that React's model of reactivity is actually "inverted".

An Example in Vanilla JS and HTML

Let's take a look at a simple form (JSFiddle):

(Be sure to open the console in your browser to watch the log.)

As you type, you should see the following output:

Rendering

C

Ch

Cha

Char

...And you'll notice that the time doesn't change.

This is because in vanilla JS, the reactive unit is the callback connected to the addEventListener; only this code is executed in reaction to a change in the UI.

If you were using web components or Lit, you would expect to see more or less the same.

An Example in Web components

The web components version is, unsurprisingly, not that different (JSFiddle):

Again, we note that the only reactive code is the one that is explicitly connected via addEventListener; none of the other code executes again.

An Example in Vue

Now let's see what this looks like in Vue (JSFiddle):

I've written it to work in JSFiddle, but it's perhaps even more obvious in Vue single file component (SFC) mode:

<script setup>

import {ref, watch} from 'vue'

const name = ref("")

const now = new Date(); // 👈 This allocation happens only once.

console.log("Rendering") // 👈 This is called only once.

// 👇 Only this reactive function is executed again.

watch (name, (val) => {

console.log(`Typed: ${val}`)

})

</script>

<template>

<label>

Your name is: {{ name === "" ? "(Start typing...)" : name }}

({{ now.toISOString() }})

</label>

<input type="text" v-model="name"/>

</template>Let's look at the log output:

This behaves just like the HTML and Vanilla JS example: the unit of reactivity is a callback; the rest of the code doesn't execute again.

An Example in React

And finally, let's look at this code in React (JSFiddle):

So what happens now when we type?

You can see that the console.log("Rendering") call gets executed on each update. This also means that the now allocation gets re-executed on each update as well (observe that the time changes on each keystroke). In fact, the entire component function is invoked again.

Experienced React developers know this, of course, so if they needed the now to be pinned, it should be moved outside of the component function or wrapped with a useMemo (if we need it in the scope of the component) as this will prevent an allocation as well.

My opinion is that React's model actually requires more experience and knowledge to do right and do well at scale because one always has to be cognizant of where to place code and/or when it is necessary to memoize results (the new compiler should improve this); React is more prone to simple mistakes of placing code in the wrong place.

Closing Thoughts

What should be clear here is that React's unit of reactivity is actually the component function itself whereas for Vue and Vanilla JS, the unit of reactivity is only the reactive function. In other words, in React, the entire component function gets invoked again as does all of the code and allocations contained in the path of that function whereas in Vue, the setup function never gets invoked again; only the reactive callback gets invoked -- conceptually the same as if we were using Vanilla JS/web components and addEventListener.

As Arek Nawo puts it, in React you opt out of reactivity whereas in just about everything else, you opt in to reactivity.

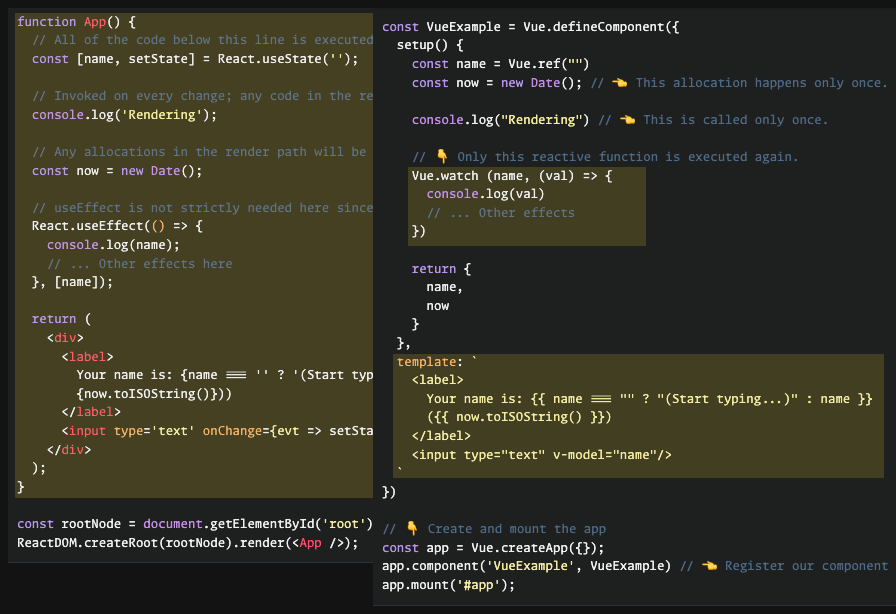

Left is the code that gets re-executed on change of name in React; right is the code that is executed in Vue

Left is the code that gets re-executed on change of name in React; right is the code that is executed in Vue

While this seems trivial and basic, this is often the root of many issues in React codebases related to multiple, unexpected entrancy of code as well as performance and memory issues when code is placed in the wrong scope (inside/outside of a component function) and also the reason why React double renders in StrictMode to expose these common code placement issues and unintended side effects.

React's model of re-executing the entire component function on re-renders and the difficulty in getting memoization correct is one of the reasons why React can easily run into performance issues at scale unless you really, really know what you're doing with respect to state management, code placement, and memoization.

As Theo and Nadia point out, the new compiler can address many of the performance related issues related to missed memoization. But to me it appears to be a bandaid applied to a self-inflicted wound; it is an inherently flawed paradigm that doesn't actually reduce complexity nor reduce defects in front-end codebases. Using a signals-based approach and only re-executing relevant callbacks would actually address this fundamental design flaw.

I think this is why if your first exposure to web applications was HTML and Vanilla JS, React always feels somewhat "off" in some way that Vue or Lit (web components) do not: the model of reactivity with React functional components is "inverted". If you're a React developer heading into Vue or Svelte or basically any other non-React framework that's based on signals or events, this is often the biggest adjustment to make (among others like effortless 2-way binding, events going up instead of callbacks going down, etc.)

If you're a Vue developer heading into React land, it is equally important to understand this difference because it strongly affects proper placement of code with implications for performance, memory, and unexpected side effects.

Addendum

The examples above were meant to be simple ones so it may not be obvious why this is problematic.

Here are two additional examples that model:

room {

lightSwitch(),

music(),

light,

carpet {

sofa {

occupant

}

}

}With these examples, the point is to understand how React and Vue (or any signals-based framework) differ in terms of how they handle re-renders on state change.

Vue Component Tree

If you play around with this example in the Result view, you'll see that when you toggle the SWITCH and MUSIC!, buttons, the different parts of the component tree render indepentently.

Here's our Vue example: (JSFiddle):

React Component Tree

This is not the case with React because of the nature of the way the reactivity system.

Watch what happens to time as you toggle SWITCH and MUSIC!.

Here's our React example: (JSFiddle):

This is solvable, though, but you must manually memoize the component:

const Carpet = React.memo(function Carpet(...) { ... }))And this is one of the problems that the React compiler will solve for.