Concurrent Processing in .NET 6 with System.Threading.Channels (Bonus: Interval Trees)

Channels are a construct that simplifies concurrent execution and pipelining of data and is often touted as one of the main draws of Go. But did you know that .NET also has built-in support for channels?

If you’re building apps that process large volumes of data or need to interact with multiple APIs for some processing job while aggregating the results, using channels can improve the overall throughput and responsiveness of the application by allowing you to execute those API calls concurrently while combining the results and/or performing post processing as a stream.

Let’s take a look at how we can use channels in C# 10 with .NET 6 and just how easy it is to implement concurrent processing with the built in System.Threading.Channels.

If you’d like to follow along with the repo, check it out here: CharlieDigital/dn6-channels

The Use Case

To start with, imagine that we are building a calendar reconciliation application. A user has two or more calendars (such as Google, Outlook, and iCloud Calendar) that we would like to read from and find conflicting events across all of the user’s calendars.

One way to do this is to simply loop over each calendar and collect all of the events:

# Pseudo code:

# Use an interval tree to hold our events and detect conflicts

var interval_tree = new IntervalTree()

do {

# API calls to get the google events; 3s

} while (has_more_google_events)

do {

# API calls to get the outlook events; 4s

} while (has_more_outlook_events)

do {

# API calls to get the iCloud events; 3s

} while (has_more_icloud_events)# Requires 10s if executed sequentially!We can use an IntervalTree data structure as a mechanism to represent the events as intervals so we can easily query to see where we have conflicts. Per the docs:

Queries require O(log n + m) time, with n being the total number of intervals and m being the number of reported results. Construction requires O(n log n) time, and storage requires O(n) space.

This gives us a pretty efficient way of checking for overlaps once we’ve retrieved all of the events from the different calendars.

The problem with this serial approach to retrieval is that each of the API calls to retrieve the events from the providers is I/O bound; in other words, most of the time is going to be spent on the network making the API call and doing this sequentially means that our program has to spend a lot of time waiting on the network.

If the calls take on average [3s, 4s, 3s], then the total time to process this operation sequentially is 10s. But if we could do this concurrently, our total operation time would be closer to 4s instead.

Why does this matter? In a serverless world, billing is very typically incurred by a compute/time metric like vCPU/seconds. So if it is possible to perform the same task in less time — especially I/O bound tasks like HTTP API calls which do not put pressure on the CPU —then there are savings in operating costs by achieving higher throughput (not to mention more responsiveness for end user interactions).

.NET provides many different options to synchronize this concurrent execution such as the ConcurrentQueue or directly using a lock primitive (like a mutex or semaphore) to control access to the shared resource (the interval tree), but today let’s take a look at a higher-level producer/consumer abstraction using `System.Threading.Channels’ which provides an easy-to-use paradigm for managing synchronization of concurrent streams of execution.

Mocking the Calendar API

To simulate this, we’re going to create a set of simple mock providers in place of actual API calls that return pages of events from Google Calendar, Outlook, and Apple iCloud Calendar (no actual API calls in this case as it would require setting up OAuth tokens!). Simulate a delay and then looping through our set of events for the provider as a set of pages as if we were pulling it from the APIs.

Simulate a delay and then looping through our set of events for the provider as a set of pages as if we were pulling it from the APIs.

Simulate a delay and then looping through our set of events for the provider as a set of pages as if we were pulling it from the APIs.

If you’re not familiar with C#, Task<> is the equivalent of Promise<> in TypeScript (or just Promise in JavaScript); if you’d like to learn more about just how similar JavaScript, TypeScript, and C# are, check out this repo: CharlieDigital/js-ts-csharp

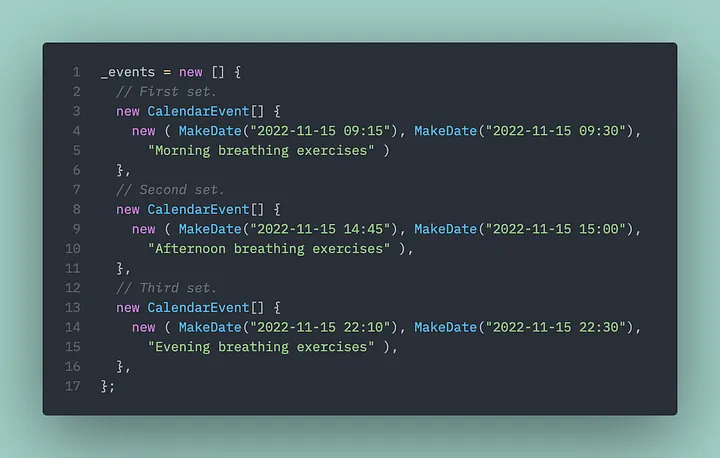

Each of our providers — just for the purposes of simulation — creates a list of events that we’ll be paging over:

Simulate returning 3 pages of events on 3 separate API calls. For conceptual clarity, I’ve just divided the tasks into “morning”, “mid-day”, and “evening” sets.

Simulate returning 3 pages of events on 3 separate API calls. For conceptual clarity, I’ve just divided the tasks into “morning”, “mid-day”, and “evening” sets.

This would result in 3 “pages” of data being returned in the call to GetCalendarEventsAsync.

(You can easily fork the code and play around with it to see how different schedules would generate conflicts.)

The Concurrent Execution

The core of the application is a simple setup of a set of concurrent calls that will use a System.Threading.Channel to communicate between the concurrent execution and the aggregation at the conflict checker in our scheduler.

We start by creating our channel:

Note that our channel is strongly typed — it accepts CalendarEvent instances

Note that our channel is strongly typed — it accepts CalendarEvent instances

Now we immediately start our Scheduler:

And set up our concurrent tasks for each of the three calendars passing in the producer side of the channel — the writer:

On lines 3, 7, and 11, we pass the writer to the providers so they can write to the channel as we retrieve events concurrently.

On lines 3, 7, and 11, we pass the writer to the providers so they can write to the channel as we retrieve events concurrently.

The code above sets up our concurrent calls; each calendar provider gets a reference to our writer.

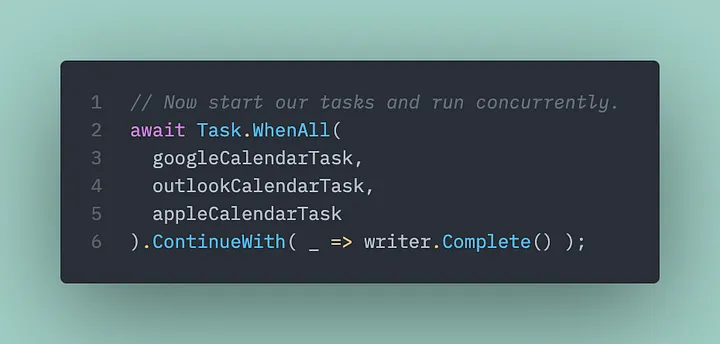

And now we wait for all of our providers to finish and then signal to our channel that writing is completed (we’ve got all the events from our calendars):

The channel includes a built-in signaling mechanism from the writer to the reader.

The channel includes a built-in signaling mechanism from the writer to the reader.

And finally, we await our scheduler to finish:

The Output

In our example, we’ll get the following output:

Note that even though we run 12 total calls (last set of calls return 0 results indicating the end of the dataset) with a random sleep up to 1s, our execution completes in only 2.566s (in this case)! Very cool and barely any work to make it concurrent!

Now let’s look at how we actually use the channel.

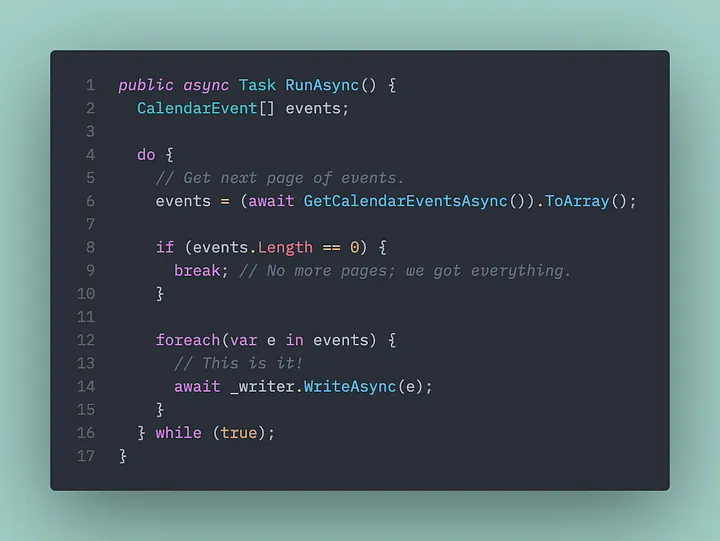

The Producer Side

This is the side that writes to the channel. In other words, as we make API calls and retrieve pages of events, we want to push those events to the scheduler via the channel.

It is surprisingly simple:

Line 14 is where we write and push our calendar events to the channel.

Line 14 is where we write and push our calendar events to the channel.

As we get events, we just write them to the channel using the writer end. Our channel is even strongly typed:

Note that our channel expects to write a

Note that our channel expects to write a CalendarEvent instance.

The Consumer Side

This is the side that reads from the channel. In this case, as our calendar event providers make API calls and return results and write them to the channel, we’re going to use the Scheduler to read from the channel and check for conflicts.

It is also surprisingly simple:

Line 3–4 are where we interact with the channel. On line 10, we add the event to the interval tree and then test on line 13 and 15 to see if we have more than 1 event in the interval.

Line 3–4 are where we interact with the channel. On line 10, we add the event to the interval tree and then test on line 13 and 15 to see if we have more than 1 event in the interval.

That’s it!

The call to writer.Complete() signals to the reading side that all the messages have been written to the channel and we can exit the loop.

Like the writing side, the read side is also strongly typed so we know exactly what we are getting from the channel.

Strongly typed with full intellisense on the read side as well.

Strongly typed with full intellisense on the read side as well.

The interval tree is a nice bonus which makes it incredibly easy to detect overlaps by simply adding the event into the tree and then querying the tree to see if we have more than 1 event for given interval.

With barely any additional effort or complexity, we’ve written a calendar scheduling conflict detection engine that can execute concurrently and retrieve events from multiple endpoints to detect conflicts!

Wrap Up

We’ve only scratched the surface with channels. It’s possible to create complex, multi-producer and multi-consumer scenarios; multi-stage data processing pipelines; and implement other high throughput scenarios using channels rather than lock-based synchronization techniques.

Processing 100k jobs; check out Michael’s article for more details.

Processing 100k jobs; check out Michael’s article for more details.

(It should be noted that the internal implementation of the concurrent storage of the Channel is actually a ConcurrentQueue)

System.Threading.Channels is one of the plethora of great reasons to consider using .NET and C# for your backend or compute intensive tasks. For I/O intensive tasks that can be run concurrently, using channels can dramatically improve performance and throughput.

If your interest is piqued, check out these past articles:

If you’re looking for more practical examples of System.Threading.Channels, check out these posts: