C# Discriminated Unions and .NET Channels

Summary

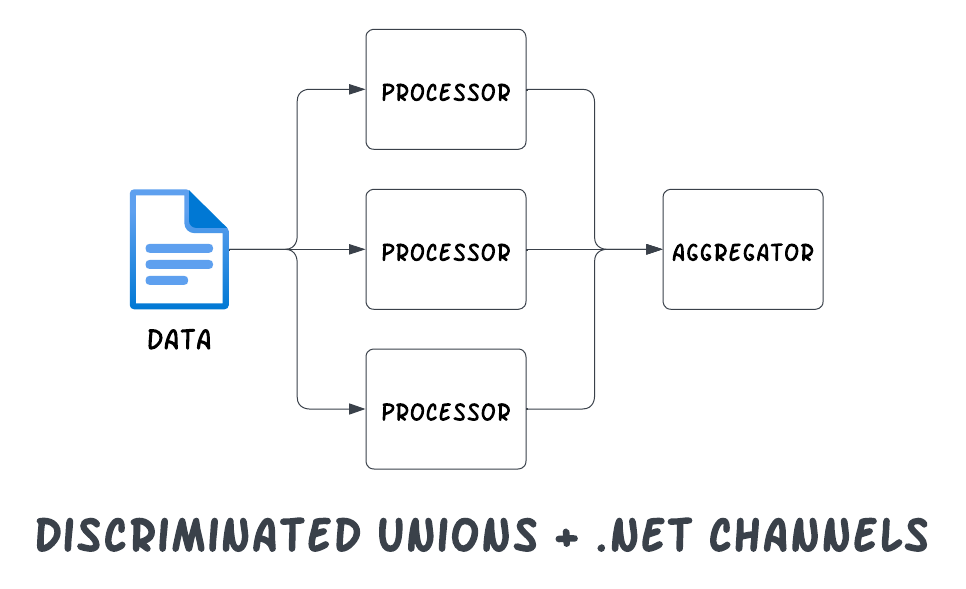

- .NET channels are an easy way to achieve high throughput, concurrent/parallel processing of information without the need to manage common challenges with thread synchronization.

- Discriminated unions pair nicely with .NET channels as a way to process and output different types of data simultaneously into one stream.

- When used together, .NET channels with discriminated unions make it clean and easy to process and combine streams of data.

💡 Full repository here: https://github.com/CharlieDigital/dotnet-du-channels

.NET and Discriminated Unions.

If you’ve used TypeScript or F# or any language that natively supports DUs, then you’re already familiar with it.

C# currently does not natively support discriminated unions as a language feature, but it has been on the roadmap now for several months (years?).

Today, it is possible to easily add DU-like patterns to your C# codebase using two .NET libraries:

Both make it easy to progressively adopt DUs in C# codebases.

There are a lot of benefits and use cases for DUs, but one of my favorites is using them in conjunction with .NET channels because it is common that there is a need to process a single record with different logic and then combine the results at the end.

Typically, the code to do so might look like this:

foreach (var record in records)

{

// Serially execute each action.

var result1 = await ProcessingAction1Async(record);

var result2 = await ProcessingAction2Async(record);

var result3 = await ProcessingAction3Async(record);

// Get all of the results and perform the final step.

await FinalActionAsync(result1, result2, result3);

}This is fine if each step is fast and cannot be parallelized. But what if each step is costly and actually discrete (no dependency on the previous result)? Processing all three steps in parallel would make better use of hardware and improve the throughput of the system.

Today, we’ll take a look at how to use discriminated unions in C# with .NET channels to achieve exactly that.

The Use Case

Imagine that the design is for a system that is processing a CSV file that has a list of call logs and the processing pipeline needs to run a series of prompts over the call record in parallel to:

- Determine the urgency of the call

- Decide which department the call should be routed to (independently of the urgency)

- Extract the keywords associated with the call so we can tag it and find it later

Since these actions are all discrete, each can be processed in parallel (e.g. using different LLM prompts) and then each facet of the call log can simply be aggregated at the end into a single record to be routed.

A perfect use case for .NET channels and discriminated unions.

The Discriminated Union

There are at least three reasonable ways to model the data structures for the flow in this case:

- Use a base class; but the various parts are mostly discrete aside from sharing the ID of the call record.

- Use a generic class like

Fragment<T>whereTis the type of the fragment, but this has some ergonomic issues when it comes to handling the actual action on the aggregation side. - Use a discriminated union!

Since three types of facets can be produced from a single call record, a discriminated union of these three types can be used to model the structure:

public record UrgencyScore;

public record RoutingTicket;

public record KeywordTags;

/// <summary>

/// The discriminated union representing "one of" the three types

/// </summary>

[GenerateOneOf]

public partial class CallLogFacet

: OneOfBase<UrgencyScore, RoutingTicket, KeywordTags>;The type CallLogFacet can be one of UrgencyScore, RoutingTicket, or KeywordTags.

It’s worth noting that there is some obvious similarity to a Fragment<T> implementation, but the DU restricts the types to only the three specific types without the need to define a base class or interface; the DU takes the place of the contract.

Setting Up the Data Source

The exact mechanism of how the call records are sourced doesn’t matter and is outside of the scope of this example. In fact, this example uses a simple enumerable that produces a sequence of numbers. (In the real world, this data might be read from a line of text from a CSV or a database):

// Our producer yields a series of async tasks. Each task processes

// one facet of the call that we want to produce metadata for.

var producerTasks = Enumerable

.Range(0, 100)

.AsParallel()

.WithDegreeOfParallelism(10)

.SelectMany(i => {

return new Task[] {

// TODO: Do work in parallel here

};

});For a range of numbers 0 - 100 (imagine these represent the 100 rows of a call center log database), the code runs some tasks in parallel to determine the urgency, routing, and keywords.

Setting Up the Channel

To support this, start by creating a System.Threading.Channel to process the records in parallel and then aggregate the information synchronously in a single aggregator.

The channel is a fitting abstraction here as it simplifies the synchronization of the parallel processing to a single thread on the read side.

In this case, the channel is created using a tuple type which has the integer representing the ID and the facet of the call log that is produced:

var channel = Channel.CreateUnbounded<(int, CallLogFacet)>();The DU type CallLogFacet allows the channel to accept any of UrgencyScore, RoutingTicket, or KeywordTags.

Main Processing Flow

The main processing flow will load the records and then start a set of concurrent/parallel processing tasks across the record set:

// 👇 Start our aggregator but do not await

var aggregatorTask = aggregator(channel.Reader);

// 👇 For a series of call records, process three facets in parallel

var producerTasks = Enumerable

.Range(0, 20)

.AsParallel()

.WithDegreeOfParallelism(10)

.SelectMany(i =>

{

return new Task[]

{

urgencyProducer(channel.Writer, i),

routingProducer(channel.Writer, i),

keywordsProducer(channel.Writer, i)

};

});

// 👇 Wait for all of the concurrent/parallel tasks to complete.

Task.WaitAll([.. producerTasks]);

channel.Writer.Complete();

// 👇 Wait for the aggregator to receive all the facets.

await aggregatorTask;Note how the producers are invoked and not awaited; they are instead simply collected as Tasks (for those more familiar with TypeScript, Task is the equivalent of Promise).

The Producers

In this case, each “producer” will simply create a class instance that represents a fragment of information (in the real world, the code might reach out to an LLM to calculate a real urgency score, routing ticket, or keywords):

var urgencyProducer = async (

ChannelWriter<(int, CallLogFacet)> writer, int callRecord

) =>

{

// TODO: Actual logic here to compute urgency

await writer.WriteAsync((callRecord, new UrgencyScore()));

};

var routingProducer = async (

ChannelWriter<(int, CallLogFacet)> writer,

int callRecord

) =>

{

// TODO: Actual logic here to determine routing

await writer.WriteAsync((callRecord, new RoutingTicket()));

};

var keywordsProducer = async (

ChannelWriter<(int, CallLogFacet)> writer,

int callRecord

) =>

{

// TODO: Actual logic here to extract keywords

await writer.WriteAsync((callRecord, new KeywordTags()));

};The Reader

And finally, the aggregator which reads messages off of the channel and checks to see if the call log has all of the parts ready. If so, then send it off for routing:

// The reader side of the channel which aggregates the facets in a

// single thread context and then sends off the call log for routing.

var aggregator = async (ChannelReader<(

int RecordId,

CallLogFacet Facet

)> reader) =>

{

var state = new Dictionary<int, CallLog>();

while (await reader.WaitToReadAsync())

{

// Read individual messages off of the channel

if (!reader.TryRead(out var part))

{

continue;

}

if (!state.ContainsKey(part.RecordId))

{

// Initialize the log if we haven't received any facets yet

state[part.RecordId] = new CallLog();

}

var log = state[part.RecordId];

// 👇 Update the log with each facet that is produced.

part.Facet.Switch(

urgency => log.Urgency = urgency,

routing => log.Routing = routing,

keywords => log.Keywords = keywords

);

if (log.IsReady)

{

// The log has all three parts aggregated; route it

Console.WriteLine($"Call record {part.RecordId} ready; routing...");

await log.RouteAsync();

}

}

};Despite the fact that the channel can produce three totally different facets of the call log, the handling of the facets on the read side is concise and clear — even though the steps are executed in parallel — because of the DU combined with the channel-based concurrency implementation.

Closing Thoughts

Discriminated unions pair nicely with .NET channels when the workload can be parallelized and each part of the workload produces a discrete result. The channel eliminates much of the complexity with synchronization when it comes to multi-threaded workloads while the DU improves the ergonomics of working with a channel that can produce multiple types of output in addition to providing an exhaustiveness constraint when aggregating the resultant fragments.

While C# currently lacks native support for DUs, libraries like dunet and OneOf provide easy-to-adopt support for DUs in C# and are a welcome tool for workloads like the one in this example.

If you’d like to read more on .NET channels, check out: